One in eight people who have had Covid-19 are diagnosed with their first psychiatric or neurological illness within six months of testing positive for the virus, a new analysis suggests, adding heft to an emerging body of evidence that stresses the toll of the virus on mental health and brain disorders cannot be ignored.

The analysis – which is still to be peer-reviewed – also found that those figures rose to one in three when patients with a previous history of psychiatric or neurological illnesses were included.

It found that one in nine patients were also diagnosed with things such as depression or stroke despite not having gone to hospital when they had Covid-19, which was surprising, said the lead author, Dr Max Taquet of the department of psychiatry at the University of Oxford.

The researchers used electronic health records to evaluate 236,379 hospitalised and non-hospitalised US patients with a confirmed diagnosis of Covid-19 who survived the disease, comparing them with a group diagnosed with influenza, and a cohort diagnosed with respiratory tract infections between 20 January and 13 December 2020.

The analysis, which accounted for known risk factors such as age, sex, race, underlying physical and mental conditions and socio-economic deprivation, found that the incidence of neurological or psychiatric conditions post-Covid within six months was 33.6%. Nearly 13% received their first such diagnosis.

The data adds to prior research by Taquet and others that showed nearly one in five people who have had Covid-19 are diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder within three months of testing positive for the virus.

In the latest analysis, the researchers found that most diagnoses were more common after Covid-19, than after influenza or other respiratory infections – including stroke, acute bleeding inside the skull or brain, dementia, and psychotic disorders.

Overall, Covid-19 was associated with increased risk of these diagnoses, but the incidence was greater in patients who required hospital treatment, and markedly so in those who developed brain disease.

The question was how long these conditions might persist after diagnosis, said Taquet. “I don’t think we have an answer to that question yet.”

He added: “For diagnoses like a stroke or an intracranial bleed, the risk does tend to decrease quite dramatically within six months … but for a few neurological and psychiatric diagnoses we don’t have the answer about when it’s going to stop.”

The likelihood that a proportion of patients who were given psychiatric or neurological diagnosis after Covid-19 had underlying illness that just hadn’t been diagnosed previously, could not be entirely ruled out – but the analysis indicated that this was not the case, he suggested.

Patients with influenza and other respiratory infections saw their doctor more often than patients with Covid-19, he said, adding that diagnoses such as an intracranial bleed or stroke could not be hidden for long and were usually diagnosed in emergency rooms.

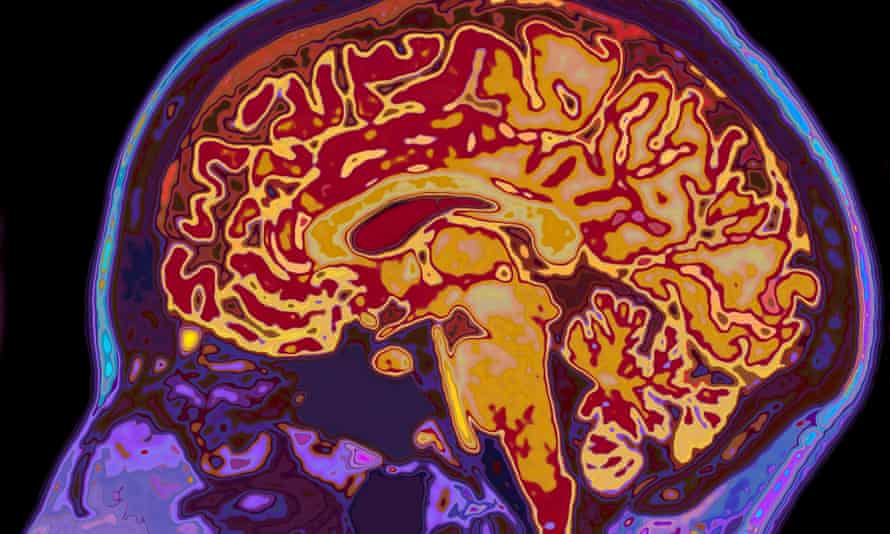

Although the study does not prove that Covid-19 is directly behind these psychiatric and neurological conditions, research that suggests the virus can have an impact on the brain and the central nervous system is emerging.

The analysis should also be also interpreted with caution, given it is possible that the first entry of a diagnosis into the electronic database might not represent the first occurrence of the condition. Such records are also typically lacking in other relevant information such as housing density, family size, employment and immigration status.

Dr Tim Nicholson, a psychiatrist and clinical lecturer at King’s College hospital who was not involved in the analysis, said the findings would help steer researchers in the direction of which neurological and psychiatric complications required further careful study.

“I think particularly this raises a few disorders up the list of interests, particularly dementia and psychosis … and pushes a few a bit further down the list of potential importance, including Guillain-Barré syndrome.” (theguardian)